In her keynote address, Cathy Berx said the following, amongst other things: “All policy and government action should start with a clear understanding of the water balance and, as such, with an objective assessment of the situation. Only then are evidence-based decisions possible. It’s also crucial for governance to be organised very well: that timely warnings are given, that there is a uniform picture and that administrators consult each other. A roadmap outlines what these consultations should entail and how choices are assessed.”

Cathy Berx, governor of the Flemish province of Antwerp (Photo: Eelkje Colmjon, Eelk.nl)

Could you explain how water management governance is organised in Flanders? Which choices have to be made and are they accepted by all the parties concerned? How does this work in practice?

Cathy Berx: “In Flanders, we use different management levels to coordinate droughts. Information sharing and advice are determined by the level applicable at a particular time. These agreements are set out in the road map on the coordination of water scarcity and drought (draaiboek Coördinatie waterschaarste en droogte), which is publicly available on the website of the Integrated Coordination Committee on Integrated Water Policy (CIW).

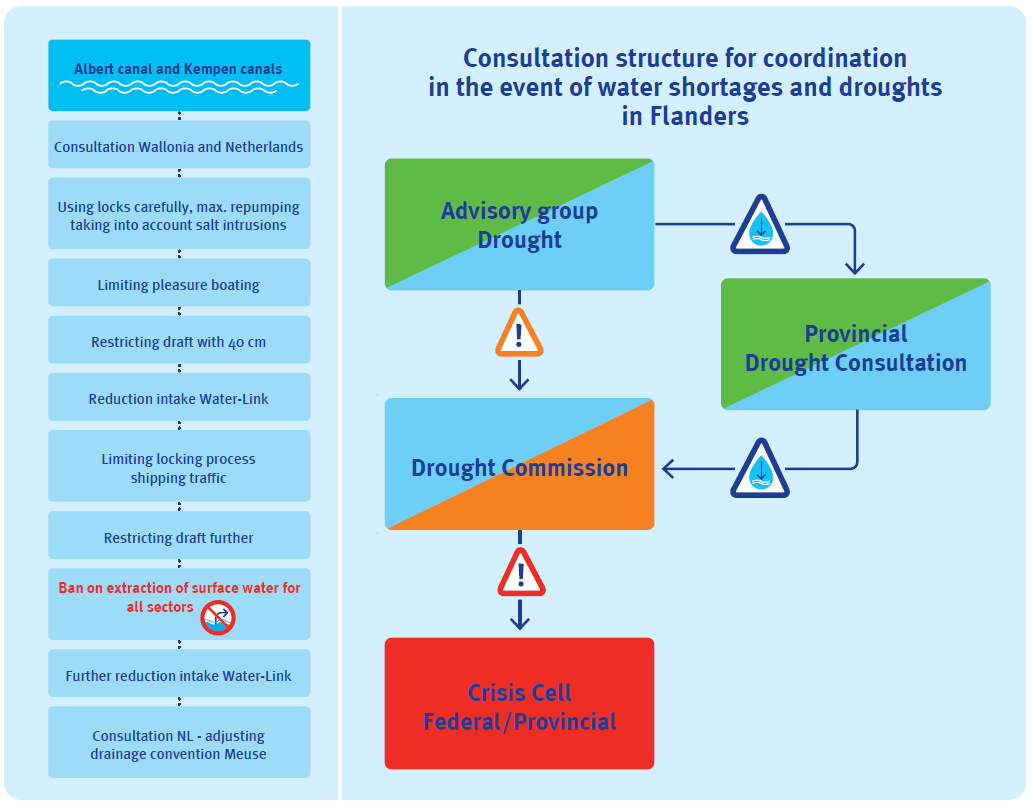

There are four consultation forums: the Drought Advisory Group, the Provincial Drought Consultation, the Drought Committee and the Crisiscel (‘Crisis Cell’). The image below uses colour codes to show which consultation forum is active at which management level. The sequence of consultations is also determined by the management level; frequency varies from monthly to weekly. It has also clearly been set out when and by which party scaling up or down is possible.

The measures to be taken are determined on the basis of the VRAG: the Flemish reactive assessment framework for priority water use (Vlaams Reactief Afwegingskader voor Prioritair Watergebruik). Generally speaking, a specific cascade of measures applies, based on a general cost-benefit analysis. It forms the basis of the VRAG. The example opposite shows the cascade established for measures on the Albert Canal.

As the governor of the province of Antwerp, I lead the provincial drought consultation, a role that logically aligns with my responsibilities in safety, public health and emergency planning. All these issues are also influenced by water quality and quantity. The importance of water for the foundation of our society cannot be overstated.

The supply of water via the Albert Canal serves significant socio-economic interests. Does the Flemish governance model help prevent potential water-use-related tensions and conflicts? If so, could you give an example?

“I’d like to refer again to the cascade of measures mentioned above. It is clearly stipulated that drinking water extraction must be avoided as much as possible and that measures that primarily impact shipping must always be taken first. To date, measures have never gone beyond the imposition of restrictions on recreational boating.

How is this administrative change an improvement compared to the ‘old situation’, before the Flemish reactive assessment framework for priority water use? Is Flanders in a better position to cope with prolonged periods of drought now? Would you also recommend this approach to other countries and regions; the Meuse river basin, for example?

“Decisions are much more scientific and data-based now, which – of course – contributes to constructive discussions. Also, clear communication takes place about the measures expected, so they can be anticipated as much as possible in advance.

Given the changing climate, the expectation is that we will increasingly be confronted with prolonged, more intense droughts. It is also likely that water levels in rivers like the Meuse will be low more often and for longer periods of time. Flanders relies entirely on Meuse water from France and Wallonia to supply water for the Albert Canal. Approximately 90% of Dutch Meuse water comes from neighbouring countries, including Germany.

The Meuse Discharge Treaty has been regulating the distribution of Meuse water between the Netherlands and Flanders since 1995. During periods of water scarcity, this treaty serves as a guideline for the balanced distribution of available water between socio-economic use in both countries and the needs of the Meuse itself. Cooperation between Flanders and the Netherlands is based on mutual trust and respect for each other’s interests.

Despite the interdependencies, no broader international agreements have been reached on the use and distribution of Meuse water in the Meuse river basin; for example with Wallonia, France or Germany.

Would you like a treaty of this nature to be in place at a broader international level? Why haven’t these agreements been made yet? Would you like to see a change in this situation?

“Of course, it would be beneficial to reach good agreements at an international level. However, as a downstream region, we don’t have the strongest negotiating position. So, a more coordinating and regulatory role for Europe would help.”

Persistently-low river flows are significantly increasing pressure for access to to scarce water. A careful weighing up of various interests is necessary. For example, drinking water, industry, shipping, energy production, cooling, agriculture, recreation and nature. This could lead to tension and conflict, both between users and between countries within the Meuse river basin.

What is your view on this? Do you share these concerns? Given Flanders’ dependence on other regions and countries for a sufficient supply of Meuse water, do you think it is important for an international governance model to be developed to coordinate water use and allocation internationally?

During droughts, we coordinate intensively with neighbouring regions. By doing this, we know what to expect and which efforts are needed to minimise water use with minimal impact. So, this coordination is effective at an operational level. However, given the expected climate extremes, it is crucial to strengthen this cooperation further.

Would a governance model like the one developed in Flanders work? Or would a different governance arrangement be more appropriate in an international framework?

“The principles of the VRAG could indeed form a basis for a European assessment framework.”

In your keynote address at the National Delta Congress, you mentioned the Flemish Drought Commission, amongst other things. The Netherlands has a similar commission. Would you consider establishing a joint Drought Commission for all the countries in the Meuse river basin?

“That would be a good idea in principle, but we currently lack the mandate to develop it. For example, the International Meuse Commission does not have the authority to initiate a development of this nature.”

What could be done to make sure this international commission is created? Which officials could make it happen? There does not seem to be a great deal of interest among the countries in question. Or perhaps the situation is not urgent enough yet for the need for this commission to be recognised? What do you think?

“An initiative of this nature should be discussed at a high political level. For example, at European level or in a ministerial meeting. Good agreements make good friends and, ideally, this discussion would happen before we are confronted with even bigger water crises.”

You also discussed international cooperation in your keynote address. Cooperation between Flanders and the Netherlands is continuing to improve; it would be good to expand it to Wallonia, France and Germany. It is interesting, for example, that Flanders shares applications for wastewater discharge permits that could impact Dutch water quality with Rijkswaterstaat (the Dutch water manager), to safeguard Dutch interests.

It would be ideal if the relevant Walloon and French authorities could share applications for wastewater discharge permits with Flanders and the Netherlands for consultation purposes. What do you think and what would need to be done to make it happen?

Could it be an option to give downstream countries and regions an advisory role in major permit applications? This would have significant added value given the crucial role of the Meuse as a source of drinking water. We must maximise our efforts to protect it. Perhaps the time has come for a new quote: ‘It’s an illusion that dilution is the solution for pollution. Protection is the key to water quality.’”

Text: Thessa Lageman, Onder Woorden

Translation: KERN Rotterdam

This interview is published in the RIWA Annual Report 2024 The Meuse